If you're starting papers with something along the lines of, "Throughout all of time and space and history..." - we need to talk.

Students stand out as mature writers among their peers when they demonstrate the ability to go beyond simply regurgitating classroom notes, textbook quotations, and stock phrases, and instead develop and refine their own original writing voices in grammatically-correct papers.

The following are five cardinal sins (as in, unforgivable) of essay writing at the high school and college levels. Avoid these to impress your professor, win over your T.A., and make me shed tears of joy:

1. The One Page "Essay" The essay should not be one long paragraph, and no paragraph should fill an entire page. If it does, go back and break it into smaller points. There are several types of essays, but there are three you can expect to write regularly in school:

Narrative: Applications, especially college applications, ask for this format. The Narrative Essay is usually first-person, autobiographical, and describes a story or process from which you have extrapolated some greater meaning or understanding.

Example: Describe a time you overcame a challenge and what you learned from it.

Expository: Expository essays explain a topic. Some research and analysis are required, and you are to make an argument. These are commonly compare-and-contrast or cause-and-effect papers.

Example: Consider the effects of video games on young people and explain whether this pastime is a positive or negative influence.

Persuasive: This is probably the essay you will be asked to write the most. As the name suggests, you are expected to take a position on a controversial (or at least debatable) topic and detail your argument, refute the counterargument, and offer evidence.

Example: Some people want the the driving age raised from sixteen to eighteen on the grounds that teenagers are not mature enough to handle a vehicle. Do you agree with this? Why or why not? 2. Disorganization

If I have to re-read the same paragraph five times and I still don't understand what you are saying, your wording needs to be reorganized.

If I have no idea what your thesis is, your introduction needs to be reorganized.

If you say you are going to discuss A,B, and C and then you never get to it, your content needs to be reorganized. Same goes for discussing A, then C, then back to A, then a brief mention of B in the conclusion.

If you close your paper with the last paragraph, rather than a conclusion, your ending needs to be reorganized. 3. Clichéd Phrasing

Cliches are sayings that we are used to hearing and reading. If your eyes gloss over when reading the following list, it's because our repeated exposure to them ultimately blunts their meaning and effect:

Throughout all time and space...

In conclusion...

But at the end of the day

All in all

Bright and early

epic battle

Wasn't that boring? I'm sorry I did that to you. Now stop doing it to the people grading your papers.

4. Filler

Filler is anything that is not immediately relevant to the topic and is an obvious attempt at padding out a weak paper. This includes ruminations on the meanings of words, quoting dictionary.com, or taking unrelated tangents.

I also warn students about poetics - if you've just written half a page about the meaning of life and the essay topic is World War II, go back and delete all of it. Then start over, this time addressing the actual assignment.

Avoid using filler by filling out a paper with textual evidence, which you can use as evidence to support the point you are making. Just make sure to explain the quote and connect it back to your overarching point. If you are just sticking random quotes in the paper, that's filler.

5. Lazy Punctuation and Grammar - Write out numbers 1-10. Do not write out years.

- Capitalize proper nouns. Do not capitalize random words.

- Do not use contractions – i.e. write out “don't” as “do not”

- Do not use "very" or "really." The sentence sounds better without it.

“The war was really devastating” vs. “The war was devastating”

- If it is a possessive, use an apostrophe.

- Avoid fragments and run-on sentences

I can't tell you how many times I've seen students write something like, "In the year of nineteen hundred and forty one, the united states entered world war II very ready to fight in the War."

Try: "In 1941 the United States entered World War II."

Shorter? Yes. But it conveys the same information without the grammatical errors, correct punctuation, and omits the filler.

Proofreading Will Be Your Saving Grace

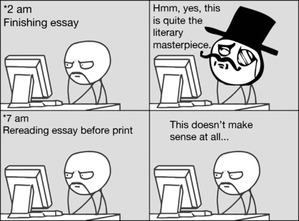

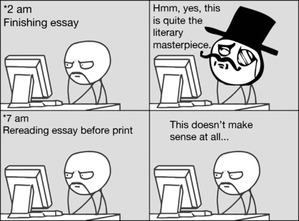

I'll end with a plea for you to proofread your papers before handing them in. Meaning, write your paper. Set it aside for at least two hours, but preferably overnight. Return to it with a fresh eye. Read it out loud. Does everything still sound as fantastic and coherent as it did when you originally wrote it?

If nothing else, you will catch the little typos, punctuation mistakes, and grammatical errors that signal to the grader you did not take the time to review the paper before turning it in.

In most cases, an error-free paper with a clearly defined argument and coherent points will receive a good grade, even if there are some gaps in the content. So please - proofread!

What is a T.A.? A Teaching Assistant (T.A.) is a graduate student who is paid by the university to assist a professor with coursework. They are almost always responsible for grading papers and exams, and sometimes help with giving lectures, running study sessions, writing test questions, and fielding students' questions regarding assignments. Is a T.A. a Professor? No. A T.A. is, however, an instructor and works with the professor to evaluate a student's performance over the semester. Usually, the T.A. is the liaison between student and professor, and is a more immediate source of help and clarification with assignments. T.A.'s are usually required to hold office hours, and can help you when your professor is who-knows-where at some obscure conference two days before the final exam.

How Do I Address My T.A.? Typically, a T.A. will have you address them by their first name - they are not professors or Dr.'s (yet). And most T.A.'s are aware of their (lowly) positions and won't put on any airs about where they stand in the university hierarchy. However, they still merit the same formalities you would use when speaking with or writing to a professor.

So...Is the T.A., Like, A Friend? T.A.'s might seem more friendly, approachable, and accessible than professors (although there are plenty of fantastic professors who also connect with their students) - but they are NOT your friend. Never (ever, ever, EVER) give your T.A. your phone number and tell them to text you, invite them to your dorm room or apartment, or ask them out on a date. You are being overly familiar and can get both you and your T.A. in serious trouble with the school. Is the T.A. My Mortal Enemy? No. I speak from experience when I say T.A.'s do not take home a stack of papers to grade with impish delight at the prospect squashing young students' hopes and dreams. It is, however, disheartening when nine students in a row think a single paragraph counts as an essay, or when they confuse something that happened in World War II with the Civil War, or when they can't even spell the professor's name correctly at the top of the page. How Do I Get My T.A.To Like Me? The same rules to get your professor to like you (or at least respect you) apply here: show up, do your homework, participate in class, respect their time, ask for help when needed, and use their office hours. T.A.'s and professors actually work together on grading, either going over papers together or working from the same rubric. If you receive a poor grade from your T.A., chances are your professor agrees with it. Or might even deduct further points. Bottom Line Personally, being a T.A. was my favorite part of graduate school. I wished MORE students would have showed up to my office hours or asked for help. But I was not immune to becoming disillusioned with students when I saw sloppy papers, a disregard for deadlines, or the hastily concocted fantastical stories for why they missed a meeting or test.

Note: We know when you're lying about your printer spontaneously combusting / contracting a 17 hour deadly virus / your great aunt dying (again).

The best students to work with were those who understood how I served as an ally for them by giving them further insight into the professor's expectations.

A T.A. can be a great ally for students, both the exceptional and the struggling, since they have the ability to empathize with students while serving as an instructor.

While it is definitely a good idea to have one or two people to proofread your resume, I would not suggest a resume-writing party. Even though it looks like they are having a great time. Photo: http://www.mticc.com For Students  Whether you are in high school or college, at some point you are going to need to write a resume. Do not just use a free template found online or through Microsoft Word. Your resume, like any piece of writing, must be tailored to the job you are applying for.

Some basic formatting guidelines include using classic fonts like Times New Roman or Arial in sizes 10-12, black and white only, printed on white or ivory quality resume paper. Although it seems counterintuitive for getting noticed, simple is better.

Basic Organization CONTACT INFORMATION

At the top, you need to state your full name and contact information, including mailing address, phone, and email.

OBJECTIVE

When you are applying for a specific job, and the hiring committee already knows exactly what position your resume is for, an objective is redundant. It is better to leave it off, and free up some room to detail your work experience.However, when posting your resume on a job site, or submitting it to a company or organization without a specific position opening, include an objective. Some people advise against including this, claiming it looks dull and "juvenile." I disagree. It is important to explicitly state what job you are applying for.

Objective: To obtain a position as an Office Assistant at Company X.EDUCATIONThen put your education history. Start with your most recent degree or certification. Include the name of the school, the specific degree and major, and the dates attended. WORK EXPERIENCEStarting with your most recent job, list your relevant work experience. Include your title, company or organization name, location, dates started and ended, and a bullet point or two outlining your major duties. You want to keep the resume to one page, so if you are waffling between which jobs to list, cut the ones that aren't pertinent to the position you are applying for. In other words, if you are applying to be a bank teller, mention that you worked as a customer service representative at a retail store but omit that you worked at a frozen yogurt shop.However, if there is a believable way to spin seemingly unrelated work experience into relevant past experience, go for it.SKILLSDo you speak a foreign language? Are you a computer genius? Refer back to the job description and highlight which of your skills fits the company's needs.REFERENCESHere list three past employers, their title, place of employment, and contact information. In some cases you can leave this off and the company will ask for them. Usually a job posting will state whether or not they want references listed. Do not write "References upon request." Putting It Together You will get conflicting advice about how to order the information I listed above. My order is intentional and strategic: you state what job you are applying for, your education, your work experience, and skills. A hiring manager is only going to skim the resume anyway; the resume should have a logical flow of information.

Whatever you do, don't lie or even overembellish. Do not put you are fluent in Japanese if you only know a few words or phrases. It's better to be up front about your abilities. Even if someone doesn't test you in the interview, you still might end up in a position that you are not, in fact, qualified for, and will be overwhelmed.

However, that doesn't mean you shouldn't try for positions that seem difficult to obtain. If you believe you are a good candidate and capable of doing excellent work, follow the guidelines I outlined and submit your resume with confidence.

For those already in the working world, I am working on a post that details how to improve your existing resume.

One final (and important!) note: for any student applying to graduate school, a professional resume is not the same as a Curriculum Vitae, or CV. A future post will cover how to write an academic CV.

There are generally three different kinds of essay prompts given on college applications:

1. The deep philosophical question

2. The experiential question

3. The "Why do you want to go to our school?" question

The Philosophical Question Gary Gaffney, ’69MS, began doctoral work in mathematics at Notre Dame but left to become an artist, eventually earning two degrees in fine art. His poem “Mil Preguntas (a meditation in 1000 questions)” explores a myriad of topics, using queries both whimsical and profound. Some of our favorites are:

• What is consciousness?

• What is your deepest mystery?

• What’s the last honest question you asked yourself?

• How often has humanity led you to forgive?

• What makes you dream?

• Is being ordinary a failure?

• What can’t you live without?

• Who convinced you about God?

• Can you tell the story of faith put to the test?

• Why should you care about the rings of Saturn?

• What will you never believe?

• What will you always believe?

Provide your own answer to one of the author’s inquires and be sure to tell us which question you select.

Big question, right? The first place to start is to make sure you read and re-read the prompt, which tells us that the applicant only has to pick one of the sub-questions to write on. How to pick? This is actually pretty simple. Mindful Writing starts with a ten or fifteen minute brainstorming session, to see what your initial thoughts and reactions are. I guarantee you will find yourself reacting to one or two of the options. Make sure you write about yourself, your qualifications, and why you want to go to the specific school you are applying for, even as you attempt to answer the philosophical question. The Experiential Question These questions are aimed at the applicant's unique life experiences and are usually something along the lines of "Describe a time in your life when you overcame a challenge," or "What is your passion and how do you live it?"

If given a choice between philosophical or experiential questions, I advise students to pick the latter. In any essay you want to offer details about yourself, and it is easier to stay focused on that task when writing about your experience.

It is important to pick an experience that was meaningful or transformative for you. Do not write about something just because you think it is what selection committees want to hear. Examples of meaningful experiences range from dealing with illness or death, living abroad, winning or losing, creating something, a hobby or interest, or a relationship. The "Why Our School?" Question Warning - this is not the easiest question to pick. Here's why - you are probably applying to more than one school. You don't really love all of them equally. There are probably one or two you really hope to get accepted into, a few you wouldn't mind attending, and a couple of "safety" schools that are better than nothing.

If you are writing the essay for your top choice, it should not be too difficult. You can mention visiting the campus, what the university means to your family, or how its programs and resources would support your future aspirations.

If you are not writing for your top choice, you need to do some research on what the college offers and why it would be a good fit for you. Final Notes The Common Application offers choices from each of the three categories outlined above, as well as a "topic of your choice." Ultimately, you need to find a way to write about something that personalizes your application and makes you stand out to an admissions officer.

It's important to remember that there are many equally qualified applicants vying for a limited number of spots at the college of your choice. Not only do you need to write well, but also, you need to write strategically, to have an advantage over other students.*

Graduate school applications require a slightly different kind of strategy, which I will cover in an upcoming post.

*If you need help writing strategically for college admissions essays. contact me about working together. I can help a client get organized in terms of forming a list of schools to apply to, preparing application essays, and looking at available scholarships.

How many times have you attempted to write while checking Facebook, LOLCats, your email, and watching Parks and Rec? How is that working for you?

According to Professor David M. Levy of the University of Washington, the problem is not technology. Rather, we need to learn how to discipline our minds to be attentive in spite of technological distractions. This Chronicle of Higher Education article details how Professor Levy uses 15 minute meditation periods to help his students practice mindfulness. "So many of those debates fail to even acknowledge or realize that we can educate ourselves, even in the digital era, to be more attentive," he says.

This idea of mindfulness is also helpful for anyone struggling with a written assignment. The worst part is starting. Sometimes after you write your name, the date, page numbers, and the title, you end up staring a blinking cursor, waiting for inspiration to hit.

It won't.

The good news, however, is you do not have to rely on inspiration or divine intervention to get a paper written.

Unlike Professor Levy, I am suggesting a more active form of meditation prior to writing. Before you even sit down to work on a paper, take 15-30 minutes to review the assignment prompt and just start writing. Write anything that comes to mind, including bullet points, questions, and possible sources to check. Make sure to consider arguments and counter-arguments if you are expected to take a stance.

When time is up, review your initial response. Is there an argument in there? If so, it becomes your thesis. If not, turn to your questions. Use these as research prompts, to help you formulate your position. Look up the sources of interest before writing, since they will usually help you be specific and detailed in your paper.

Then you can sit down to start the paper. By now you have a mental roadmap of where your paper is heading.

Mindful writing requires two main steps for most of us:

1. Unplug from all distractions (even email!).

2. Devote a block of time to just thinking about the paper.

Mindful writing is not intuitive for most of us. We are busy and used to dividing our attention to several things at once. Give it a try, or contact me for further help. Writing can be efficient if you start with a rough outline. Then you can get back to "liking" your friend's vacation pictures on Facebook.

|